In an early episode of her podcast, Burnt Toast, Virginia Sole-Smith joked about starting a regular segment called “Can my kid eat that?” where the answer would always be “Yes!” A self-described anti-diet journalist, she wasn’t really joking: “I get a version of this question every single week, so I’m going to keep answering it.” How many days per week can a 2-year-old eat ice cream? “There are seven days in a week. Your child can have ice cream seven days a week. There is no law against this.” What about a 13-year-old who, left to their own devices, would eat an entire box of Oreos? “Pour a glass of milk — so they can dunk them?”

“Oreos come up a lot, man,” Sole-Smith says, laughing while snacking on a bowl of Cheez-Its in her home office in the Hudson Valley. “I mean, I like Oreos fine, but it’s really the fact that you’re not letting yourself have Oreos that makes it feel like Oh my God, I’ll be powerless over them.” She seems more amused than exasperated, though she finds herself repeating this point often — that restricting food only makes us more obsessed with it. A 41-year-old mother of two, she knows her generation has been programmed to believe that allowing their kids unlimited access to sugar and processed foods is unhealthy or even bad parenting. A central premise of her work is that, actually, it isn’t.

I’m a parent of a toddler, and my Instagram feed is full of advice from pediatric dieticians and guides for introducing your baby to kale and branzino. When I first came across Sole-Smith’s newsletter about how we’d all be better off if we chilled out about what’s in our kids’ lunch boxes, it felt like a relief. Since launching Burnt Toast on Substack in 2021, Sole-Smith has gained a following among millennials who recognize that they’d rather not pass on their screwed-up relationships with food and with their bodies to their kids. “We all know the diet culture we grew up with in the ’80s and ’90s did a lot of damage. We don’t want to be like our moms with their point counting,” she says. The problem is that most parents are still deeply afraid of having fat kids.

After publishing her first book, The Eating Instinct, about the U.S.’s cultural relationship to food, Sole-Smith heard from a lot of parents who were trying to do better. “It was clear that they really wanted their kids to feel good about their bodies and have a healthy relationship with food and not get eating disorders — but also to be thin,” she says. It’s not hard to understand why: Her reporting documents the many ways the world is horrible to fat people — children included. But she’s convinced that real progress isn’t possible until we all start to recognize and unlearn our anti-fat bias. Her new book, Fat Talk: Parenting in the Age of Diet Culture, argues that if we really care about raising healthy and happy children, we need to get over our fear of fatness.

Even before my daughter was born, doctors instilled in me the fear that I might make her too big. When I was diagnosed with gestational diabetes, my OB warned that if I didn’t follow a strict diet, the baby would gain too much weight, putting us both at risk for birth complications. The assumption that weight corresponds directly with health is reinforced at every pediatrician appointment, which typically begins with a weigh-in and assessment of where your child falls on the growth chart. And if it weren’t already clear where doctors stand, the American Academy of Pediatrics recently doubled down on its commitment to fatphobia: The organization’s new obesity guidelines recommend diets for kids as young as 2 and weight-loss medication and surgery for adolescents.

If you’ve grown up alongside messaging about the “childhood-obesity epidemic,” it may come as a surprise that the link between weight and health is far less straightforward than we’ve been led to believe. In Fat Talk, Sole-Smith lays out a robust body of research debunking the idea that high body weight alone is a cause of negative health outcomes. “The real danger to a child in a larger body is how we treat them for having that body,” she writes. That’s because it is clear that experiencing weight stigma is associated with all sorts of health issues including heart disease, diabetes, and high cholesterol. Making kids (or anyone) feel bad about their weight — including subjecting them to weight-loss interventions — is not only cruel but demonstrably bad for their physical and mental health.

Sole-Smith wants her readers to understand that there’s no harmless way to keep pursuing thinness — for your child or yourself. She knows it’s a tough pill to swallow. Her inbox is full of emails from women who read her newsletter but find themselves getting stuck. “A lot of them say, ‘I totally get what you’re saying. I don’t want to discriminate against people. But I personally cannot give myself permission to be fat, because I feel better if I’m thin,’” she says. “They’ll attribute it to health, but what they really mean is ‘Society makes my life easier when I’m thin.’”

By obsessing over thinness, Sole-Smith argues, we’re complicit in upholding a pervasive system of oppression with deep roots in racism and classism. But somehow, reading her work still feels more comforting than confrontational. She wants to help us recognize our biases — not to make anyone feel bad. “If I make every thin white woman feel like shit, they’re not going to engage and we’re not going to get anywhere,” she says. Sole-Smith knows that fatphobia is all around us, and she’s not offended by the fact that most people have internalized it. “I try to help people understand that it’s actually not about you,” she says. “I really fundamentally believe it’s a ‘hate the game, not the player’ situation.”

Her own evolution on these topics has been a multi-decade process. She grew up in Connecticut, where her dad was a political-science professor at Yale and her mother worked in insurance. As a thin kid, she didn’t feel like her body was viewed as a problem. “I was a really picky eater,” she says. “I lived on, like, spaghetti, peanut butter and jelly, turkey sandwiches, and strawberry yogurt until I was about 12.” She feels lucky her parents weren’t pushy or panicked about it. But she still had the sense that for the adults in her life, weight was something they had to think about a lot and manage. “When I came home from my freshman year of college, both my parents noticed in subtle ways that I had gained weight,” she says. “They weren’t harsh about it, but it was like, ‘Oh, your shorts are fitting differently.’”

After graduating, Sole-Smith spent the early 2000s writing weight-loss stories for women’s magazines like Glamour and Marie Claire. “That was a time where we weren’t calling them diet stories anymore. We were calling them ‘wellness’ or ‘portion control.’ ‘Eat smarter.’ ‘Eat whatever you want but not sugar,’” she says. Even then, advising women on how to change their bodies didn’t sit right with her. But her real shift of perspective came after her daughter Violet was born in 2013. At 1 month old, Violet stopped eating as a result of medical trauma and had to be put on a feeding tube.

Over the next year, Sole-Smith and her husband struggled to help their infant regain interest in food. “I’d spent my whole career trying to map out rules for how we eat,” she says. “They were all predicated on the idea that someone else knows better than you and if you follow these rules, you will be thin, you will be happy, everything will work.” But when Violet refused to nurse or take a bottle, even her doctors were at a loss. In the end, the approach that worked wasn’t about pressuring or rewarding her to eat. Instead, they had to help Violet relearn how to listen to her internal hunger cues — and trust her to decide when and how much she wanted to eat.

Trusting children to listen to their bodies is now a defining principle of Sole-Smith’s work. Having a baby with a feeding disorder, she learned firsthand that “obsessing over it doesn’t fix it — it makes it worse.” Even for parents fighting far more mundane dinner-table battles, research shows that exerting too much control over what your kid eats — whether it’s pressuring them to eat vegetables or restricting sweets — usually backfires. So what does “healthy eating” for kids look like? When it comes to feeding her daughters, who are now 9 and 5, Sole-Smith’s priority is respecting their autonomy. “It’s the power to say no, to be curious and try new things, and to decide when and how much they want to eat.”

Photo: Yael Malka

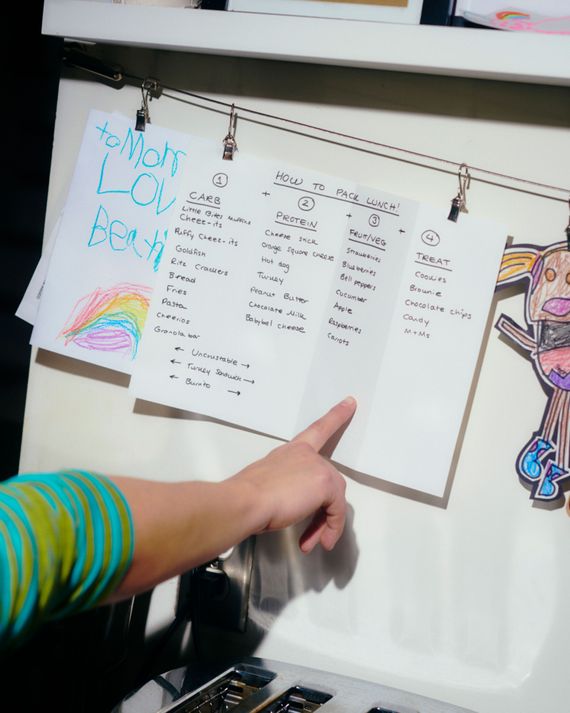

She has accepted that the reality of life with young children is sometimes that they eat Cheerios for three meals per day, and it’s fine. “Vegetables are the least important part of it to me,” she says. “They have their whole lives to decide if they want to eat kale.” Her pantry is stocked with Puff’d Cheez-Its, Extra Toasty Cheez-Its, and Goldfish — “Yes, that’s three different kinds of orange crackers” — plus Girl Scout cookies and Chewy chocolate-chip granola bars. A handwritten list of “Family Dinner Rules” hanging in the kitchen includes “No pressure/Listen to your body” and “You don’t have to earn dessert.” It’s not that she doesn’t care at all about nutrition, but she’s convinced that fixating on it leads nowhere good. “We know from research that the nutrition piece tends to work itself out,” she says. “If we’re serving a variety of foods, over the course of a week, kids will hit a lot of different food groups.”

That moms make up the majority of Burnt Toast’s 28,000 subscribers isn’t surprising. “Women are held to more rigid body ideals and parenting ideals,” Sole-Smith says. “We’re socially conditioned to be the ones who make the meal plans and worry about picky eating, and then worry when the pediatrician says they’re too high on the growth chart.” Fat Talk makes clear that our dysfunctional relationship with food is tightly wound up in misogyny and assumptions about motherhood. According to Sole-Smith, in almost every interview she has done with someone who struggled with disordered eating, they mention something their mother said or did that made things worse.

That’s not to say dads have no role in this: Sole-Smith writes that when she asked her readers what was stopping them from taking a nonrestrictive approach to food with their kids, the most common answer was “my husband.” She says a lot of the pushback she gets comes from men. “It’s like a greatest-hits album that they play: ‘It’s bad parenting.’ ‘It’s lack of willpower.’ ‘It’s people who are lazy and don’t care about eating well or exercising.’”

“I sometimes joke that my role in all this is to bring the thin white women along,” Sole-Smith says. It doesn’t bother her that her audience is mainly women: They’re the ones who are open to the change she’s advocating, which is deceptively radical.

For me, the permission to stop stressing about how often my 2-year-old eats only French fries for dinner has been a welcome relief. But after years of telling myself to just eat salad or jog a few more miles, I know I’m still a long way from viewing my body or my daughter’s with anything approaching neutrality. Truly relinquishing control is hard to do. “If you give up chasing weight loss, you invite in all of the shit that comes with being a fat person or even with being a less-thin person,” Sole-Smith says. But she has convinced me that it’s worth it to keep trying. The way she sees it, it’s really about the willingness to give up a little bit — or a lot — of privilege. She knows that’s scary. “But it’s also incredibly liberating.”

More Stories

Hanco’s: Bringing the Flavors of Vietnam to Brooklyn

TropiBowls Bring Healthy Food to Tamarac • Tamarac Talk

How can we make our brains prefer healthy food? – study